Hongxing Xuan Paper Mil

April in Anhui brings mild temperatures and willow tendrils swaying in the breeze. The awakening springscape makes this the most inviting season for visitors. Yet for the papermakers of Jing County, Xuancheng, it’s also the optimal time for crafting xuan paper—the humidity is just right, neither too hot nor too cold, ensuring ideal production conditions. The renowned Hongxing Xuan Paper Mill stretches along the Wuxi River in Jing County’s outskirts. On south-facing slopes nearby, straw materials dry in the sun, destined to become paper. Through repeated boiling in alkaline water and sun exposure, the previous year’s harvested rice straw sheds impurities, leaving behind pure white fibers called liaocao (“scorched grass”). Blended in varying ratios with treated bark from blue sandalwood trees, these fibers yield different grades of xuan paper: Tepi (highest sandalwood content, most expensive), Jingpi, and Mianliao—each tiered in price and purpose.

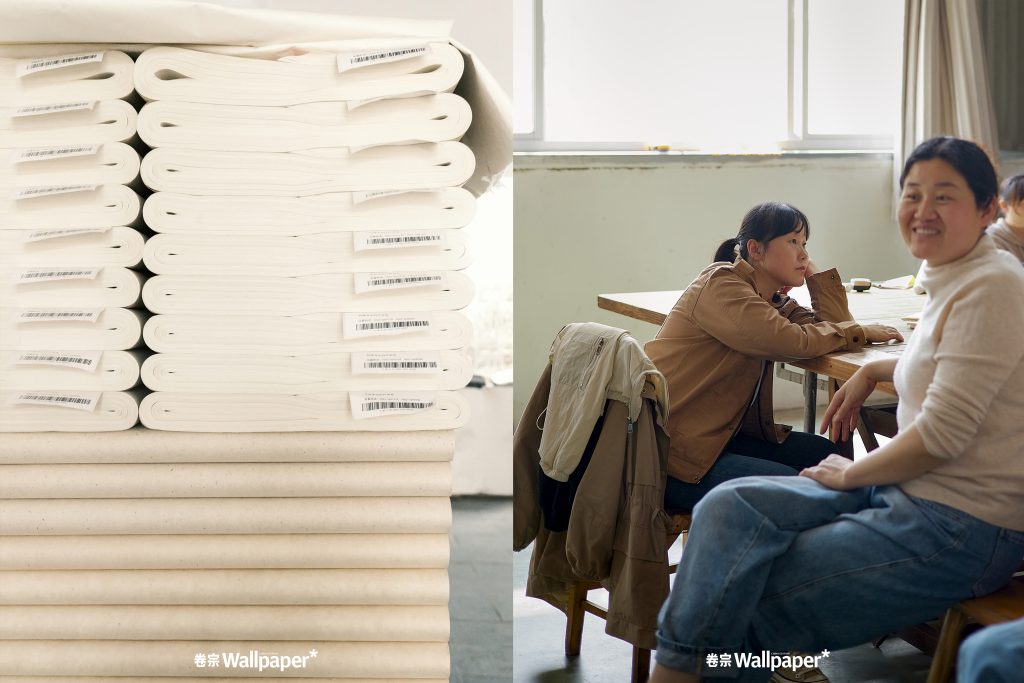

The mill houses a Xuan Paper Cultural Park and Museum, where visitors witness the craft’s iconic processes. Workers pound pulp with wooden mallets, weave bamboo screens for sheet-forming, and demonstrate drying and trimming—all with hands-on opportunities for guests. Since demonstration takes priority over output, laborers often complete most tasks by noon, reserving light workloads to engage tourists. During lulls, they rest in workshops but spring into action at approaching footsteps, like clockwork automata in a living diorama of tradition.

The production of “San Zhang San”—a colossal xuan paper sheet made only once or twice a year—coincided with our visit to Jing County. From early April through the month’s end, crowds gathered for this rare chance to witness the mill’s artisans at work in their raw, unfiltered element. By 6 a.m., lights already glowed in the sheet-forming workshop. Workers had filled the vats the night before; now, at dawn, they mixed pulp to precise ratios, blending in a viscous additive extracted from wild kiwi vines (paper catalyst). This solution ensured that stacked damp sheets could later be separated—rehydrated after drying—without tearing. Yet for oversized sheets like San Zhang San, achieving such flawlessness demanded near-impossible precision. No instrument could measure the ideal balance of pulp, water, and catalyst. Instead, artisans relied on instinct, test-lifting one or two sheets to gauge weight and thickness. Like alchemists of fiber, they adjusted by touch, their hands calibrating an invisible science passed down through generations.

On the second floor of the Xuan Paper Museum, rows of precious Qing Dynasty and Republican-era xuan paper are displayed—their edges faintly yellowed, yet their beauty and texture undiminished by time. Paper endures a thousand years”—so goes the ancient praise for this craft, a testament to the resilience of plant fibers tempered by sun and rain. But behind that resilience stands an uncelebrated lineage of workers who have devoted their strength and patience to this ever-evolving tradition, never once turning away. Most of them have never used the famed Hongxing xuan paper they helped create—not for calligraphy, not for painting. Their hands shape immortality for others’ art, while their own stories remain unwritten on its surface.

On lazy afternoons, they unscrew their thermos flasks, take a sip of tea, and lean against the wall or slump into chairs, their minds adrift in quiet exhaustion. By four o’clock, they begin their journey home. Sixty kilometers from Wuxi, Taohua Tan (Peach Blossom Pond) still bustles with visitors today. When Li Bai boarded his boat and left Jing County all those centuries ago, who knows if the verses he penned were written on some of the earliest sheets of xuan paper? And as Wang Lun stamped his feet in farewell song on the shore, did the waters lapping at his feet once nourish the fields of a papermaking family? People come and go like flowing water, leaving no trace—while xuan paper endures, carrying stories far beyond a single lifetime.

The lighting technician from Henan Province

At 4 a.m., while rural Henan still lingers in predawn slumber, migrant lighting technicians from Yanling are already at work. Their day begins in darkness: hauling equipment from warehouses, loading trucks, driving to film sets, and unloading hundred-pound gear before the first hint of daylight touches the sky. The textbook definition calls them “lighting designers”—artists who sculpt shadows and illumination to serve a visual narrative. But behind the camera, these unsung workers remain shrouded in the very darkness they battle. Their calloused hands rig the lights that make stars glow on screen; their silent footsteps trace paths no audience will ever see. Cinema’s magic demands invisible sacrifices. The beams that caress an actor’s face or conjure a sunset are held aloft by arms that tremble with fatigue. Yet in the credits, their names flicker past like afterthoughts.

A typical commercial shoot means one relentless cycle for lighting assistants: a 3 a.m. to 3 a.m. grind of physical labor. The heaviest workload falls before and after filming—hauling stacks of equipment, coiling cables like serpents, and rigging scaffolds—but the real test is precision under pressure. During takes, they pivot on command: adjusting a lamp’s tilt by five degrees, dialing in a 200K color shift, or softening shadows without a whisper of noise. All while the gaffer (lighting’s field general), wired into an earpiece, orchestrates light like a conductor—negotiating with cinematographers, producers, and actors to translate vision into photons.

This was once a test of brute strength. Before wheeled cases and hydraulic lifts, assistants muscled hundred-pound fixtures across sets, their shoulders bearing the weight of an industry’s expectations. It’s why the role long skewed male, with job ads demanding one non-negotiable trait: “吃苦耐劳” (endurance beyond fatigue). ear grows lighter, the demands haven’t. Every flawless shot still rests on backs bent in the dark.

Li Guang, now a Director of Photography, began his career as a lighting assistant—one of the first lighting technicians from Yanling, Henan, to venture into Beijing’s film industry in the 1990s. At the time, China’s cinema sector was nascent and faced a shortage of talent. Like many others from rural Henan villages where farming alone could not sustain livelihoods, Yanling witnessed a wave of migrant workers seeking opportunities elsewhere. Amid the boom in Qing dynasty-themed dramas, Li Guang—newly arrived in Beijing and under 20—wandered the streets and noticed casting calls for extras. To make ends meet, he joined them. “You could spot them instantly,” he recalls. “A crowd with shaved foreheads—all extras.” After working as an extra, Li Guang entered the world of film lighting. Back then, gaffers were either graduates of film academies assigned to state-owned studios or professionals from Hong Kong and Taiwan. These individuals possessed technical expertise and academic credentials, commanding status equal to or higher than cinematographers—they were called “Lords of Light” (灯爷). Migrant workers from Henan, however, could only observe and learn through grueling physical labor, steadily accumulating experience and skill. The Beijing Film Studio frequently used lighting equipment left behind by Italian filmmakers during the production of The Last Emperor—bulky and heavy fixtures. When filming on remote locations unreachable by vehicles, every piece had to be carried by hand.

Admittedly, Foucault’s theories focus more on the soft technologies embodied by human subjects under the lens of power. Yet with the rapid rise of digital-age technologies, the very meaning of “technology” seems increasingly alienated. While frontline technical laborers—the “B-side” of technology—pervade every facet of human society and shape the minutiae of daily life, their visibility often fades precisely when it matters most. Today, even amid transformative shifts in labor structures and a slowdown in the growth of labor supply at elevated levels, China—as the developing world’s most populous nation—still relies on its vast frontline workforce as a vital engine of economic growth. Nevertheless, these grassroots technical workers remain paradoxically unseen: indispensable yet overlooked architects of our technological reality.

Lanxiang Vocational School

Lanxiang Technical Institute sits at the foot of Yaoshan Mountain in western Jinan, three kilometers north of the Yellow River. Like most Chinese economic development zones, the area clusters with warehouses, logistics hubs, machinery plants, auto parts suppliers, and building material firms—a landscape devoid of scenic charm, quietly utilitarian. Following roads uniformly named Lanxiang Middle Road and similar variants—guided by the ubiquitous slogan “Where to master skills best? Shandong Lanxiang leads the rest!” (a broader evolution from its earlier “Excavator skills? Shandong Lanxiang thrills!”)—we arrive at Shandong Lanxiang Technician College. Renamed in 2017 from its former title Shandong Lanxiang Advanced Technical School, it appears largely indistinguishable from other urban vocational institutes across China, save for its sheer scale. skills.”

Students at Lanxiang often clarify to outsiders: “We teach more than excavators.” While its iconic excavator program falls under Engineering Machinery Operation & Maintenance, the institute boasts seven other flagship fields:Automotive Inspection & Repair / Culinary Arts & Nutrition / CNC Machining / Welding Technology / Computer Applications & Maintenance / Rail TransportRumors claim “95% of China’s excavator operators graduated from Lanxiang”—a wild exaggeration. Yet since its founding in 1984, the school has trained well over 500,000 students, now working across every sector imaginable. According to 2022 data released by China’s Ministry of Education:The nation’s vocational education system offers over 1,300 specialized programs across 120,000+ program locations, comprehensively covering all sectors of the national economy. Between 2012 and 2022, vocational institutions produced 61 million high-skilled graduates—equipped with both technical expertise and professional competence. 70% of new frontline workers now emerge from vocational schools.

We all seem to relish discussing Lanxiang. Yet behind its status as a national punchline lies a sobering reality: the systemic stigmatization of China’s vocational education. Workers once celebrated as revolutionary heroes in the early PRC era now endure uneasy scrutiny—their value measured and diminished by shifting social metrics. The 1992 end of the planned economy shattered the worker’s symbolic prestige; their image no longer aligned with newfound ideals of “success.” Workers once celebrated as revolutionary heroes in the early PRC era now endure uneasy scrutiny—their value measured and diminished by shifting social metrics. The 1992 end of the planned economy shattered the worker’s symbolic prestige; their image no longer aligned with newfound ideals of “success.”

American anthropologist David Graeber famously branded modern white-collar jobs as “bullshit jobs”—labor devoid of substantive value. Contemporary China intensifies this paradox: we endure not only meaningless work but also a frenzied rat race within such environments. Faced with this reality, masses of youth adopt forced “Buddha-like detachment” (foxi) or outright choose “lying flat” (tangping). “Retire early” has become the collective sigh. In this post-Fordist era, even scrolling through short videos in bed unconsciously enrolls one in the assembly line of the digital economy. As Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argue in Empire, contemporary labor relies on self-organization among workers—forged through communication, collaboration, and “biopolitical labor” that creates affective bonds between them.Rather than fearing ChatGPT’s potential to displace human labor, we must confront a more urgent question when examining institutions like Lanxiang: How do we forge anew the bonds between laborer and laborer?

This International Workers’ Day, Wallpaper magazine dedicates its “Ballad of Labor” feature to three field studies, spotlighting the frontiers of tangible technologies: Xuan paper artisans in Jing County, Xuancheng, Anhui. Lighting technicians from Yanling, Xuchang, Henan. Vocational trainees at a technical institute in Jinan, Shandong.

Here, we salute them—

the hands that build our world.